Recounting The Great Chicago Fire Of 1871

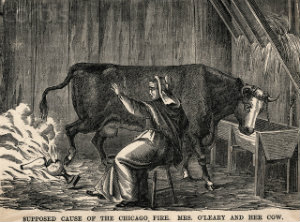

The Cause Of The Great Chicago Fire

Chicago experienced a very dry summer in 1871 that left the ground arid and the wooden city exposed. It was on October 8, 1871, on a Sunday evening just after nine o’clock, when a fire broke out at 137 De Koven Street (on Chicago’s West Side) in Patrick and Catherine O’Leary’s barn. The couples’ neighbor saw flames licking up from their cow barn and shouted as much as he could in a bid to alert the people. The firefighters, tired from fighting a huge fire the previous day, were first directed to the wrong area. When they finally reached the O’Leary home, they found the fire fierce and raging out of control. Who would have thought that it would bring about what is known today as the Great Chicago Fire.

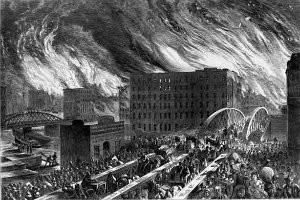

The Raging Inferno Ravages All

In an hour’s time, several poor shanties were ruined and the fire, with the wind’s help, began to move east and north, toward downtown. As warehouses and factories caught fire; they fueled even bigger flames. The heat got bigger and bigger and eventually rose, driving cooler air down. Then, the super-heated columns of air began to twirl and build what was described as “the fiercest Tornado of Wind ever known to blow here” by former mayor William Ogden. Even if the atmospheric wind was approximately 30 miles per hour, these spinning columns of fire blew wilder, tearing the roofs off buildings and hurling them hundreds of yards into the air.

Chunks of blazing wreckages were emitted across the Chicago River and several hours later, the South Side was ablaze. Just a few hours later, another chunk of flaming wood was tossed across the river and landed on a kerosene tanker on the North Side. The residential, wood-constructed North Side was doomed. Wood burned, stone was reduced to dust or collapsed and crumbled into rubble. Wooden houses, commercial and industrial buildings, and  private mansions were all consumed in the blaze.

private mansions were all consumed in the blaze.

The Fire Is Put Out At Last

On the morning of the 10th, it finally began to rain fall and the flames were at last extinguished. At least 300 succumbed to the fire with 100,000 being left homeless and $200 million worth of property was ruined. The whole central business district of Chicago was flattened. It is no wonder that the fire was one of the most outstanding events of the nineteenth century.

The commission investigating the cause of the fire concluded their investigation nine days later after questioning 50 people. All testimonies made over 1,100 handwritten pages and were used in the issuing of the inconclusive report about the fire’s cause. They exonerated Catherine O’Leary by asserting that: “Whether it originated from a spark blown from a chimney on that windy night,” it read, “or was set on fire by human agency, we are unable to determine.” Nevertheless Catherine O’Leary remained culpable in the public’s eye. The O’Leary cow story became a legend to date.

The Aftermath of the Inferno – Catherine The Recluse

That Catherine O’Leary’s cow had knocked over a lamp in her barn that started the fire was a rumor invented by journalists who later acknowledged their slander. However, it was too late for Catherine O’Leary, as she became a recluse – leaving her home only when dire need arose, until her demise in 1895.